“If one of the ancient Dutch burghers should visit Flatbush today, he could never be made to believe that this is the same spot where he was born, worked, prayed, loved, suffered, and died. His dear old Midwout is gone – to all intents and purposes wiped off the face of the earth, and in its place there has sprung up something so entirely different and strange, and uncongenial to his taste that he would be glad to get back to the other side of the Jordan as fast as his ghostly wings could carry him.”

– John Snyder, Tales of Old Flatbush, 1945

In the late nineteenth century, as the sleepy town of Flatbush transformed from farmland to booming suburb, residents became increasingly concerned with chronicling the history of the area.

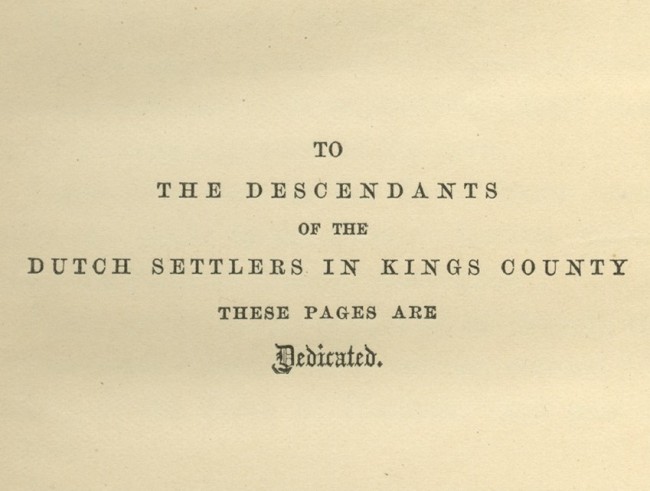

Gertrude Lefferts Vanderbilt dedicated her 1881 book, The Social History of Flatbush, to Kings County's Dutch settlers.

Members of the Lefferts family had long documented their own family history through writings, genealogies, and records of marriages, deaths, and births. But Gertrude Lefferts Vanderbilt (1824-1902), a talented amateur historian, took on this project with new urgency. Over the course of her life, she wrote several books and articles on the history of her family and of her hometown. Her most celebrated work, the 1881 book The Social History of Flatbush, revealed rich insights about the lives of Dutch Brooklynites. Gertrude made it clear that her historical writings were motivated by the rapid disappearance of “old Flatbush.” “There have been great changes in this little town,” Gertrude wrote prophetically. “The day is probably not far distant when [Flatbush] will become a part of the adjoining ; then all traces of its village life and its individuality as a Dutch settlement will be lost.”

In February 1918, the Lefferts family's Flatbush homestead was relocated to Brooklyn's Prospect Park.

In the early twentieth century, Flatbush developed at an even more rapid pace. The generation of Leffertses that followed Gertrude struggled to reconcile their longing to preserve their heritage with their desire to profit from valuable real estate holdings. In 1917, the estate of John Lefferts, Jr. (1850-1905), Gertrude Lefferts Vanderbilt’s nephew, agreed to donate the family’s Flatbush homestead to the city of New York on the condition that it be moved to Prospect Park. A number of Brooklynites formed the Old Dutch House Preservation Committee, raising almost $15,000 to fund the relocation.

Early in the morning on February 13, 1918, the house was moved several blocks to its new home in Prospect Park. In 1920, the Daughters of the American Revolution opened the home as a museum. Today, Prospect Park Alliance continues to operate the house as a historic site open to the public.

Learn More

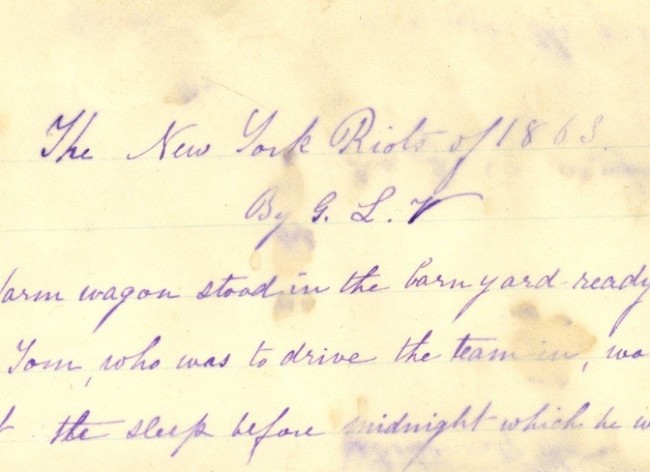

Analyzing Gertrude Lefferts Vanderbilt’s chronicle of New York’s 1863 Draft Riot

The Vanderveer mill, where members of Flatbush's African American community gathered during the 1863 New York Draft Riots

Gertrude Lefferts Vanderbilt witnessed many of the tumultuous events that took place in nineteenth-century New York. Among the most infamous was the 1863 Draft Riot, the largest insurrection in American history after the Civil War itself. In reaction to a law allowing men to pay a $300 commutation fee to avoid the Union Army draft, working class New Yorkers (many of them Irish) looted the city, taking out much of their anger and frustration on black New Yorkers. Many African Americans sought refuge from the carnage across the East River in Kings County. In Flatbush, black residents fearful that the violence might spread gathered together at the Vanderveer mill, a Flatbush landmark, seeking strength in numbers.

Three decades later, Gertrude Lefferts Vanderbilt recorded her experiences during the riot in a short essay entitled “Account of the Draft Riots of 1863.” Gertrude portrayed black New Yorkers as sympathetic victims of the riot, decrying the “vindictive and malignant spirit of the mob” and its aggression towards “the most helpless class of the community.” Reflecting a deep nativism that many generations of Leffertses expressed, Gertrude blamed “the lower class of our foreign population” for the insurrection.

Yet even while she criticized the violence of the riots, Gertrude also articulated a condescending racism towards Flatbush’s black population. She portrayed African Americans as passive and pitiable figures, “guileless and simpleminded, gentle and kindly in their feelings, and grateful for sympathy offered them.”

Throughout her life, Gertrude Lefferts Vanderbilt considered herself a foremost advocate of African Americans, devoting her energies to organizations like the Society for the Amelioration of the Colored Population of Flatbush. Yet as well meaning as she was, her perspectives were influenced by the pervasive racism of the time and by her elite class background. Her recollections demonstrate the complex intersections of gender, class, and racism in one nineteenth-century woman’s worldview.